While on holiday in Jerez last year I visited the Bodegas Tradición. As well as a fantastic tour of their cellars and a taste of some amazing Sherry, I learnt that they also have a very special art collection. This collection, commended for the quality of the Spanish paintings it contains, should also be highlighted for its beautiful frames. I will probably do several blogs on their frames, but the first is on a Dutch Ripple frame around a painting of Jesus.

Dutch ripple frames are a term to describe ebony veneered frames that have a distinctive repetitive ripple across its surface. The wave can either be flammleisten (from side to side) or wellenleisten (undulating) (1). The frame surrounding Jesus is primarily of the latter. It is usually also a black lacquered finish. However, the ripple became identified with other wood colours as the aesthetic was adopted but made in for cheaper substitutes (2).

The style has often been linked with Protestant Holland of the 17th Century because of its stark finish (lacquered black). Yet this does not explain its position here on a painting of Jesus from Spain during the height of the Catholic Spanish Empire. Dutch ripple was prevalent in fact throughout North and South Netherlands, parts of Germany, and Spain (3). There are two common threads that link these areas and this style; Hapsburg rule and the VOC (Dutch East India Company).

Ebony, quite opposite to the notion of reserved religion, was expensive, exotic and novel. It was first imported into Europe in the early 17th Century through Holland by the VOC who had discovered it in their holdings throughout South and South East Asia (4). While being Northern Dutch in origin the company had many German and Sourthern Netherland shareholders (5). This was Hapsburg ruled Europe and meant that this material was most easy to source through this economic network and could explain its popularity in Hapsburg ruled Spain.

As testament to the cost of ebony it was only ever used as a veneer on frames. This poses a serious of difficulties with creating varied and ornate designs. Flat fields were of course easy as shown in the picture above, but what about adding decoration? Technology of the day did not allow for fine gold plasterwork we now associate with antique frames (Compo needed to create these styles was not invented until the early 18th century in France (6). Decoration had to be hand carved and then plastered as required. Ebony is very hard, making carving difficult but also as a veneer cutting deep enough to make the extra labouring worthwhile was not possible. The solution to decorative design was ‘Dutch Ripple’ or more appropriately flammleisten and wellenleisten.

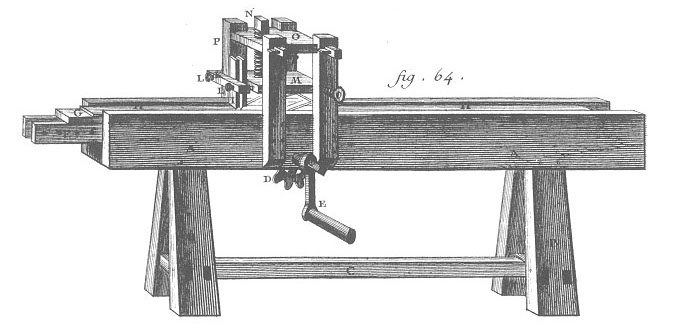

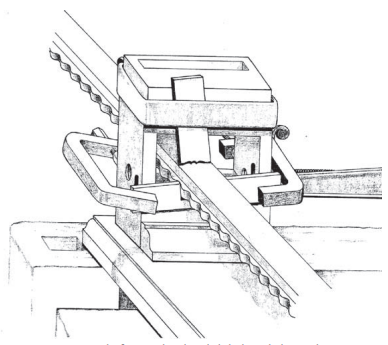

The machine that was developed to produce the intricate ripple designs was simple in principal, although I am sure very technical to create consistent lengths. Several have been recreated recently using images and descriptions from later versions of the technology detailed in Diderot’s Encyclopedie and Joseph Moxon’s “Mechanick Exercises” (1678-80) (7). The best example can be seen with Kurt Nordwall at the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The machine itself was probably already used extensively to create standard moulding shapes, such as ogees and scoops, in cheaper woods. The principal idea was to have a fixed planning blade held above a bed through which wood is fed. The top surface would be scraped off as the wood passes underneath. This would be repeated a number of times, deeper with each pass, until the wood length matched the shape of the blade. To make the wellenleisten ripple an eccentric wheel is added to the bed to make the wood length undulate up and down increasing and decreasing the distance from the blade in a consistent rhythm. To create flammleisten (side to side) a jig was made which has a horizontal cut wave in the side. As this passes through the cutting block it is forced to move right and left to pass through.

Ebony is not nowadays a practical or sustainable material for frames, but we do produce a frame in the spirit of the Dutch Ripple frames of the 17th Century. Made of pine and hand finished to recreate the glories of ebony, our frame continues the long tradition of wellenleisten. We can of course finish it in any colour you may desire, but we prefer to recreate the ebony sheen typified in the frame from Bodegas Tradición to keep the richness and opulence of the Dutch Ripple alive today.

0118 948 1610

0118 948 1610